|

Historical Index:

Childhood; Cape Observatory; Astronomer Royale; Achievements; Career; Personal

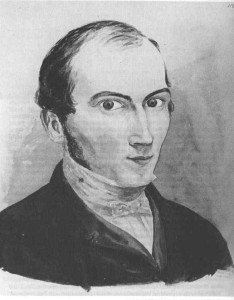

Smyth’s Childhood.

There was a close relation between Smythe and the Director of the Cape Observatory, Thomas Maclear. “While living at Bedford, Maclear had made the acquaintance of the Smyth family, whose head, Admiral Smyth, had served in the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars. The old Admiral was very much of a character – to put it kindly, he was an eccentric …Smyth married the daughter of a British merchant who lived in Naples, and naturally made various Italian friends. One of them was the astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi, who had acted as director of the Palermo Observatory in Sicily, and had achieved fame in 1801 when he had discovered (and named) the first asteroid or minor planet, Ceres.

It was from his meeting with Piazzi that the Admiral’s interest in astronomy dated. On his retirement to Bedford he armed himself with the best instruments he could find and they were very good indeed – and became a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society. He also published some astronomical books, one of which, the Cycle of Celestial Objects is still regarded as something of a classic. To quote a contemporary reviewer: “The descriptions of the various objects are enlivened with a vast amount of general classic and antiquarian lore, introduced in the most genial spirit.”

When the Admiral’s next son (second son) arrived, the name chosen was Charles Piazzi Smyth. This was predictable; but less predictable was the fact that for a long period this same son would become a staunch assistant to Maclear at the Cape – and that eventually he would become the second Astronomer Royal for Scotland.” Copied from Moore, pp. 48 – 49.]

Time at the Cape Observatory.

Meanwhile at the Cape Observatory the directors had a problem in finding reliable assistants. Fallows (previous director) had assistants, but they did not however had the title of Assistant Director. Their names were James Fayrer, Patrick Scully, William Ronald, James Robertson and Reverend John Fry. The first person with the title of Assistant Director was William Meadows who also left. Maclear was in dire need of a reliable assistant and appealed to the Admiralty for help. When Charles finished his schooling his father considered him to be a worthy candidate. Such was Admiral Smyth’s influence with the Admiralty that young Charles was appointed assistant to Maclear (director at the time) at the age of sixteen, and he arrived at the Cape on 9 October 1835. This was very fortunate as Smyth turned out to be the first reliable assistant director at the Cape Observatory. [Warner – Astronomers, p.49.] He was 17 years old when he arrived at the Cape. [Smits]

Smyth inherited from his father a robust physique, great stamina, and a natural inquisitiveness. He was known for working eighteen hours a day. Due to Maclear’s friendship with his father he treated Smyth as his own son. Smyth also had a good relationship with Herschel and was frequently invited for “tea and stars.” Herschel was even on occasion obliged to apologise to Maclear for having detained his assistant for so long. [Warner – Astronomers, p.49.]

In 1839 a second assistant was appointed at the Cape Observatory. William Mann filled this post.

Smyth on occasion had a less than happy working relation with Maclear as Maclear tended to be “bossy”. For example, in 1843 Smyth took the Herschel 14 ft telescope outside the building onto solid ground in order to observe a comet. This was a logical move as the telescope was mounted on a wooden floor in the observatory, which made it unstable. Maclear, who was in the field to re-measure the Arc of the Meridian, heard about this and ordered “that all enquiries of a physical description with regard to the Comet are to b thrown overboard; that the 14 feet reflector is to be replaced in the Telescope room; and that nothing is to be done but the determining of the place of the Comet.” Smyth and Mann started thereafter to refer to Maclear as “The Emperor”. [Warner – Astronomers, p.58.] Smyth later published an article: a note on the stability of wooden floors for telescope mounts. [Warner – Astronomers, p.60.]

The Observatory was situated on a very barren terrain. The local farmers claimed that the summers were too hot and dry for anything to grow. Smyth was undaunted. In 1836 a pump was sent out from England and fitted to a windmill of his own design. “Then began its pumping operations, and they were continued ever after during my residence at the Cape, pumping to the top of the hill a continuous stream of about 400 gallons (1 818 litre) an hour.” This changed the landscape at the Observatory and formed part of Maclear’s efforts to make it more hospitable. Smyth published an article in 1852 in the Practical Mechanics Journal on the pumping operations at the Cape. [Warner – Astronomers, pp.60 – 61.]

Astronomer Royal for Scotland.

Thomas Henderson, previous director of the Cape Observatory who became the Astronomer Royal for Scotland, died on 23 November 1844. With the strong urging of Herschel the post was offered to Smyth. He accepted the post but stayed on at the Cape to help Maclear finish some of the survey work. (For the Arc of the Meridian project) Smyth left the Cape on 22 October 1845 to take up the post. In Edinburgh Smyth completed Henderson’s work and made numerous meridian observations of his own. [Warner – Astronomers, p.60; p.62.]

Achievements.

Smyth was also an excellent artist. Many of the visual details we have of the Observatory, and the Arc of Meridian project, comes from Smyth’s drawings and caricature sketches.

He was also a pioneer in photography and published the first book with stereoscopic pictures and constructed a remarkable miniature camera. (After he left Cape Town) His collotypes, discovered in the archives at the Royal Greenwich Observatory and at the Royal Society at Edinburgh, provide the earliest extant photographic illustrations of Cape scenes. [Warner – Astronomers, p.58; p.62.]

He became an outspoken advocate of mountaintops for the sights of large observatories – a consequence of his experiences at Cape ranges. [Warner – Astronomers, p.62.]

Piazzi Smyth was recognised as a leading spectroscopist [Warner – Astronomers, p.62.]

Career:

1835 to 1845: Smythe was chief assistant at the Royal Cape Observatory to Maclear.

-Astronomer Royal of Scotland. [Smits]

Personal:

1819: Born in Naples. [Smits]

1900: Died

Charles Piazzi Smyth was a strange mixture. He was an excellent practical astronomer, but he was also obsessed by “pyramidology”, and he believed that mankind’s destiny had been foretold for those able to read it by the arrangement of the chambers and other features of the Great Pyramid in Egypt. When analysed, the arguments he put forward are shown to be weird in the extreme; nevertheless, they started a cult which has never really died out”. [Copied from Moore, p. 49.]

Piazzi Smyth inherited from his father a robust physique, great stamina, and a natural inquisitiveness. He was known for working eighteen hours a day.

A glimpse into the character of Smyth can be seen in the extract of the following letter by Eardly-Wilmot to Mrs Maclear, after he and Mann visited Smyth in Edinburgh in 1847: “Mann will tell you all about Smyth, his old style of indifference to any personal comfort remains. His house is furnished with considerable taste; but he appears perfectly indifferent as to whether he eats or drinks or sleeps – they all appear to be necessary interruptions which he makes as short as possible. [Warner – Astronomers, p.60.] Seen against this background Smyth must have disliked the interruptions he experienced whilst at the Cape. Piazzi Smyth stated that serious work in the main building was continually interrupted since families with children lived on the grounds. “The consequence is, that while there may be a family of no more than ordinarily rackety children, transit observations are continually interfered with for 12 hours of the 24, a noise of passage as if made in the room; they find their way in & play with the mercury (in the artificial horizon troughs), & at hide & seek behind the instruments, & up and down the steps.” [Warner – Astronomers, pp.61 – 62.] |

Remaining Artifacts:

.

Pictorial:

Photographs:

(Museum Africa acq. no. P/302 & P/234)

Lithographs: (Museum Africa)MA346

MA 43/838

MA 43/839

MA 43/840Sketches: (possibly same as Lithographs)

Maclear’s survey tent (Museum Africa) [Moore p. 62.]

Two sketches of La Cailles’s northern point. (Museum Africa) [Moore pp. 60 – 61.]

.

Bibliography:

Laing, J.D. (ed.), The Royal Observatory at the Cape of Good Hope 1820 – 1970 Sesquicentennial Offerings, p.18

Moore, P. & Collins, P., Astronomy in Southern Africa, pp. 48 – 49. (General Source)

Smits, P., A Brief History of Astronomy in Southern Africa. (Unpublished)

Warner, B., Astronomers at the Royal Observatory Cape of Good Hope.

.

By Smythe:

-Letters: (Museum Africa MA 52/1092 – 1095)

Archival:

AFRICANA MUSEUM, JOHANNESBURG [JHA8, p.218.]

-Letters from C. Piazzi Smyth (assistant to Maclear, later Astronomer Royal for Scotland) to his sister (all written from Edinburgh 1846-62) (Ref. 52/1092, 3,4,5,5A).

-Original drawings by C. Piazzi Smyth-see Catalogue of pictures in the Africana Museum by R. F. Kennedy.

LIBRARY OF THE SOUTH AFRICAN TRIGONOMETRICAL SURVEY, MOWBRAY, CAPE TOWN [JHA8, p. 220.]

-Smyth: Sketch book of C. P. Smyth showing panoramas made 1842-43 from various survey stations on extension of Lacaille’s arc. |