| GILL, David [KCB; FRS][Sir]Professional Astronomer

Born: 1843, Aberdeen, Scotland. |

|

|

|

|

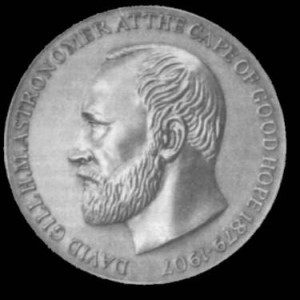

| Famous for: Director of the Cape Observatory: 1879 – 1907. Pioneer of Astro photography. Gill and Mouchez, the director of the Paris Observatory, convened the world’s first international astronomical meeting in Paris—the “astrographic” meeting in 1887— which Culminated in the Carte du Ciel Project. Speciality was angular distance measurements. He made some of the worlds most accurate measurements before the space age. Designed the Reversible Transit Circle. Most transit manufacturers have since copied his design. Gill award. This is South Africa’s highest award in the field of Astronomy (named after him). . Summary: David Gill was one of the most remarkable astronomers in the history of Southern African Astronomy. When Gill took over, the Observatory was outdated. He set out to modernise the facility and when he retired, the Cape Observatory was one of the finest and best equipped observatories in the world. Gill pioneered astro photography and did an incredible amount of work towards establishing photographic catalogues of the Southern Sky. The projects that Gill started still kept two directors preceding him busy. He was also a remarkable person outside of the field of astronomy, as the personal section attest. |

|

|

|

|

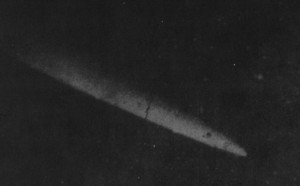

| History: David Gill became interested in Astronomy before he was ten years of age, thus before 1853. (Born 1843: Look personal section.) [Moore p. 72] 1863: In his spare time he helped Prof. Thomson at Kings College to set up an old transit instrument and to establish an accurate time server. 1866: Gill built a small observatory with a 12-inch telescope that he made himself. After school Gill went into the family business & was a clock and watchmaker for two years -some of the time spent on the European Continent. During this time he acquired a feeling for precision instruments, knowledge of business methods and foreign languages, which were to be useful to him later as an astronomer. [Laing, p. 12.] “On 18 May 1869, at a time when photography was still in its experimental stage, Gill took a picture of the Moon. It can safely be said that it was this achievement – the photograph was an excellent one, even by later standards – which drew attention to the young amateur and started him off on the career which was to bring him international fame, and provide astronomers all over the world with a priceless new research tool.” [Copied from Moore p.73.] (+/- 1870) Lord Lindsay of Dun Echt (13 miles from Aberdeen) saw Gill’s photograph of the moon. He was an aristocrat who used his money to build a private observatory, equipping it on a lavish scale with instruments finer than many of those available in Government Observatories. After meeting Gill he offered him the post of director. [Laing, p. 12.] At Dun Echt he made some of the best ever measurements of angular distances to stars. “One of the instruments provided for his use was a 4-inch heliometer. As Gill’s future observational measurements were to be made largely with this type of instrument, it may be as well to say something about its structure and use. In a heliometer, the object glass is cut in half, so that one half may be made to slide past the other, giving a double image of the object under study. It is used to measure very small angular distances as seen through the telescope. Gill’s great skill in the use of precision instruments, which was innate and which had been further developed during his watch making days at Besancon, helped him to make this device peculiarly his own) and indeed his results remained among the best ever obtained right up to the era of space-probes. After a night spent in using the heliometer, Isabel used to say that he would come into the house shouting and singing “as if he had gone daft”! [Copied from Moore pp. 73 – 74.] 1874: Gill went with Lord Lindsay to Mauritius to observe the transit of Venus. This was a privately sponsored expedition to observe the transit, and Gill was the chief observer. The results were disappointing. [Sheenan p. 35] 1877: Gill joined the Royal Astronomical Societies’ sponsored expedition to the Ascension Islands. He observed the opposition of Mars and calculated a very accurate sun / earth distance. (Astronomical Unit) His value was within 0.2 percent of the modern accepted value. [Sheenan, p. 36; Koorts – British, pp. 55 – 56.] 1879: Due to Lord Lindsay’s prompting, Gill was appointed Her Majesty’s Royal Astronomer (Director) at the Cape of Good Hope. Before he took up his post, he extensively travelled Europe in order to meet some of the world’s foremost astronomers. He visited Paris, Leiden, Copenhagen, Helsinki, Pulkova and Strassburg. 1879 (June): Gill arrived in Cape Town. 1881 – 1883: Gill privately acquired the Dun Echt Heliometer from Lord Lindsay. Gill’s tasks at the Cape were to: [Laing, p. 12.] -wipe out all arrears of reductions. -recondition existing instruments. With the Repsold Heliometer, Gill (with co-operation from Northern Hemisphere observations) determined the solar parallax of three minor planets, Iris, Victoria and Sappho. The value that he used of 8″. 80 were used in the computation of all almanacs, up to 1968 when radar echoes methods and data from the mariner probe refined the value to 8″. 794. [Laing, p. 13.] Gill used the Repsold Heliometer to measure the distances to a number of Southern stars. His accuracy was later confirmed by photographic observation methods. [Laing, p. 13.] In 1882 another transit of Venus took place and South Africa was idealy placed to observe the event. The British appointed Stone, previous director of the Cape Observatory, to organise the British expeditions. As part of British efforts the transit was observed from four sights in South Africa, and there was also an American expedition to Wellington. Gill was placed in charge of organising the expeditions locally. [Koorts – British, p. 41, p. 43; Koorts – Huguenot, pp.199 – 200.] To help solve the timing problems (accurate timing is essential) Gill pionered the placing of observing sights next to telegraph lines. [Koorts – British, p. 41.] In 1882, Finlay, an astronomer at the Cape Observatory discovered a bright comet in the southern sky, which became known as the ‘Great Comet of 1882′.. By this time the ‘dry plate’ cameras were newly introduced. Gill, remembering his Moon photograph of 1869, invited a local photographer, Mr Allis and they fastened a portrait camera to the clock-driven equatorial telescope. They took several photos and the results were astounding. The photographs showed a good image of the comet, but the background stars were also shown with absolute clarity and sharpness. [Koorts – British, p. 51.] The more he studied the photographs, the more he realised the use of photography for making star-maps down to very faint magnitudes. Gill sent the results to a few institutions, including the Royal Astronomical Society, Royal Society, and the Paris Observatory. Gill also ordered a larger lens from Dallmeyer, the famous optical worker. [Moore pp. 75 – 76.; Smits] These photographs of the comet would motivate Gill to start one of the most ambitious projects of his career. The result was the famous CPD or Cape Photographic Durchmusterung, which extended a Northern Hemisphere survey, the Bonn Duchmusterung, down to the South Pole of the sky. The finished catalogue gives the brightness and approximate positions of nearly half a million southern stars. [Moore p. 76] Carte Du Ciel. The Paris Observatory was interested in creating it’s own map of the sky, and enlisted the help of Gill. “Even while work on the CPD was going on, a larger and even more ambitious project was put in hand by the Paris Observatory. This was nothing less than a photographic chart of the whole sky, showing stars down to the fourteenth magnitude. In addition there was to be a catalogue giving the precise positions of all stars down to the eleventh magnitude – more than a million stars altogether. A scheme of this kind could be carried through only with the co-operation of many astronomers and many observatories. As the acknowledged “father of astrography“, Gill was prominent both in the organising and the carrying-out of this great work. His many friendships among astronomers, made or strengthened during his “grand tour” before he had set out for the Cape, now stood him – and the Carte du ciel, as the project was called – in good stead. A major portion of the work was carried out at the Cape Observatory, and a fine new telescope, the astrographic refractor, was acquired. Yet in spite of the devotion of Gill and his colleagues, work on the Carte du del was not completed until a few years ago. The whole concept was simply too big for late-19th century facilities.” [Copied from Moore p. 79] 1900 (May 24): Gill was knighted. Gill designed the reversible transit circle, which has become the pattern for most of the transit circles made since. Gill achieved a variety of impressive things outside of the field of Astronomy. See “Personal Aspects.” 1906: Due to ill health, Sir David and Lady Gill retired in London. (Note: According to Moore p. 91, Gill was Director until 1907. I presume he was considered Director until a replacement was appointed) career:

Personal: Other Personal Aspects: List of Titles and Honours bestowed on David Gill [Gill – title page]

|

|

|

|

|

|

Link to the Telescope Manufacturers. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Link to the Main Bibliography Section and more information about Sources. |

|

| Remaining Artifacts: Gill Medal. This is South Africa’s highest award in the field of astronomy. Street named after him. The Republic Observatory street address is Gill St, Observatory, Johannesburg. Photograph Africana Museum [Laing; Moore p. 72] . Bibliography:

By Gill: Archival: SOUTH AFRICAN ARCHIVES, ROELAND STREET, CAPE TOWN [JHA8, pp. 220 – 221.] SOUTH AFRICAN MUSEUM, GOVERNMENT AVENUE, CAPE TOWN [JHA8, p. 222.] The Archives of this Museum contain extensive correspondence on Museum matters by Sir Thomas Maclear and Sir David Gill, both of whom were Trustees. CAPE OF GOOD HOPE ROYAL OBSERVATORY PAPERS IN THE ARCHIVES OF THE ROYAL GREENWICH OBSERVATORY [JHA 9 pp.74 – 75] -David Gill (1879-1907). |

|

|

|

|

| Related Internal Links: Royal Observatory at the Cape of Good Hope. . Related External Links: Historical Astronomical Posts in Britain and Ireland Encyclopedia Brittannica: The Bruce Medalists: David Gill |

|

Gallery

The Great Comet of 1882, discovered by Finlay. This photo, taken by Gill, was the first ever photograph of a comet. It led Gill to the realisation that phototgraphy can be used as a method to study astronomy, and from this realisation the first photographic star catalogues were made, for example the Cape Photographic Catalogue and the Cape Photographic Durchmusterung. Gill is considered as one of the pioneers of astrophotography.

Photo taken by Gill. Source: Moore.