Historical Index: Transvaal Meteorological; Transvaal; Union; Republic; Amalgamation

Transvaal Meteorological Department:

There was no Observatory in the Transvaal (previously a Republic and later a province in South Africa) and the climate was superb. On 29 October 1902, the South African Association for the Advancement of Science petitioned the Government to establish an observatory in or near Johannesburg, “for the collection and distribution of meteorological observations throughout the Transvaal Colony”. Although astronomy was mentioned it was deemed that meteorological aspects were more important. [Hers; Smits]

On 17 December 1902 the Assistant Colonial Secretary, W H Moor advised that the project had been approved. He invited David Gill from the Royal Observatory, Cape of Good Hope, to assist with “securing the best man available as Director of the department”. Gill suggested R TA Innes as Director, a most interesting and capable person. [Hers] (Look Astronomers: Innes)

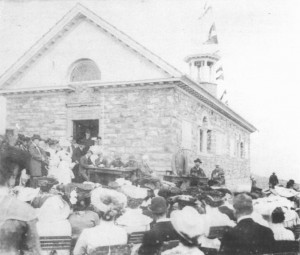

The Transvaal Meteorological Department started operating on 1 April 1903, but only officially came into existence on 17 January 1905. Lord Milner performed the opening ceremony.

Sir Herbert Baker, well-known South African architect, designed the Observatory buildings. A house was also designed for the Director, although this building was not built until 1910. [Hers]

Transvaal Observatory:

The name was changed in 1909 to the Transvaal Observatory. [Personal communication with Vermeulen]

Meteorology was the first concern, and in the beginning, astronomy played only a minor role, until S.A. became a Union (1910). When the four states (Transvaal, Orange Free State, Cape and Natal) merged into the Union of South Africa, their meteorological services were combined into the Union Meteorological Department. Only then could the Transvaal Observatory devote its time to astronomy. (South Africa became a Union in 1910, but the name change to Union Observatory only took place on 1 April 1912.) In 1907 the observatory required its first telescope, and with Innes as a pro-astronomy Director, the transition started towards astronomy.

The Observatory started with the unusual step of receiving its first telescope on permanent loan basis from the Royal Observatory, Cape of Good Hope. [Laing, p.4] (“The first astronomical instrument erected on site was a 2 5/8-inch refractor, loaned to them by Dr. Oskar Buckland, for use with the International Latitude Program” [Smits, p.16.] More info needed)

Installation of a 9 inch telescope in 1907. In 1924 this telescope was renamed the Reunert Telescope. [Smits]

Union Observatory:

The Observatory achieved its greatest fame during the time that it was known as the Union Observatory (1912-1961). The Directors were known as Union Astronomers, there were four:

–Innes (1903-) 1912-1927

–Wood 1927-1941

–Van den Bos 1941-1956

–Finsen 1957-1961 (-1965)

The National Time Service for South Africa was stationed at the Union Observatory. Jan Hers was put in charge of this department. The old Meteorological Observatory was changed into a building housing the clocks, as well as a seismometer. Later on the time service was taken over by the CSIR, and after the Observatory closed, it moved to other premises. [Smits] See Time Signals

1923: Agreement between Leiden and Union Observatories whereby the facilities of the two institutions were made available to each other. Since the night sky in the Transvaal is much better than in Holland, most of the observers went from Holland to South Africa. (This eventually led to the establishment of the Leiden Southern Station.) [Moore, p.107; Smits, p.20.]

1938: As part of the agreement between Union and Leiden Observatories, the Union Government provided funds for building new facilities on the terrain. This was to house the Rockefeller twin 16-inch telescope, which belonged to Leiden, but administered by Union Observatory.

Due to growing light pollution problems in Johannesburg, Leiden decided to move to a new sight at Hartebeespoort. (Look Leiden Southern Station.) The agreement was that Leiden Observers operated Hartebeespoort, but it was an official outstation of the Union Observatory. As such it came under Finsen’s jurisdiction even though it was virtually autonomous. (director was Walraven) The Rockefeller twin and 10 inch Franklin – Adams telescopes were moved to Hartebeespoort, even though the latter was the property of the Union Observatory.

Republic Observatory:

In 1961, when South Africa became a Republic, the name was changed to the Republic Observatory.

In 1964 it became part of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (C.S.I.R.)

During 1962 – 64 a new office block with a library was erected, with two domes on its roof. The Reunert– and Franklin Adam twin telescopes were moved here. [Hers]

It was planned to built a 74-inch telescope, and to this end a mirror blank was ordered. This telescope never materialised. [Moore, p.104; Smits] (This proposed 74 inch telescoped must not be confused with the Radcliffe 74 inch telescope)

The Lowell Observatory International Planetary Patrol started in 1969. It ran for five years and was virtually the death blow to the Observatory double star observing. van den Bos and De Klerk tried for a short while to share the Innes refractor with the patrols program, but this was not successful and all double star observation came to a halt. [Personal Communication with G. Roberts who worked at the Observatory.]

Amalgamation:

The South African Government decided to amalgamate all astronomical research into one body, which later became known as the South African Astronomical Observatory (S.A.A.O.). This meant that the Republic Observatory had to close down. “The first official rumblings came on 23 September 1970, when the CSIR authorities announced that there had been agreement with the British Science Research Council for the setting-up of the combined South African Observatories; the Cape would be the headquarters and Sutherland the outstation, 235 miles away across the Karoo, with Sir Richard Woolley as Director. This meant – as we have already noted – that the main Cape telescopes would be moved to Sutherland, while the Radcliffe Observatory at Pretoria would be dismantled altogether. But what about Johannesburg?” [Copied from Moore, p. 104.]

This decision met with great opposition. “In an article in Nature, dated 29 January 1971, van den Bos wrote as follows: “The 26.5 inch refractor, with which the Observatory built up its reputation in double star observation, is little, if at all, affected by sky illumination or smog and the time-tested ‘seeing’ remains as good as ever. There is no reason why it should not be usefully employed at this work, at its present site, for many years to come . . . Even if the observatory were moved en bloc to Sutherland it would remain more than doubtful whether its largely astrometric programmes could be continued there as successfully as in Johannesburg or Hartebeespoort . . . The minor planet work would be seriously affected by transfer from the clear winter skies of the High Veld, of that there is no doubt, for it is in winter, when the ecliptic is south of the equator, that the programme reaches its peak. Furthermore, double-star work in particular is of an intensive, long-term and personal nature.”

Finsen was in full agreement that to close the Republic Observatory would be a tragic miscalculation – and he was not alone in his views. Yet in many ways the situation was curious; after Finsen’s official retirement as Director in 1965, no successor had been appointed and although the programmes were being continued much of the impetus had gone.

Other arguments also were advanced. Killing the Republic Observatory would leave South Africa’s largest city without any major astronomical institute and presumably the Library, second only to that at the Cape, would also go. Shifting the 26.5-inch itself would have been impracticable even if it had fitted into the proposed programme for Sutherland – which it did not. The situation was still fluid when the International Astronomical Union, the controlling body of world astronomy, met in 1972 (it meets every three years; the 1972 venue was at Brighton, in England). Misgivings were expressed by the Commission’s dealing with minor planets and with double stars. In the official report published after the congress there was a comment from Dr P. Herget, the famous American asteroid observer, to Dr F.J. Hewitt, Vice-President of the CSIR in Pretoria: “There have been more observations of more minor planets made at the Johannesburg Observatory (and the annexe at Hartebeespoort) than at any other observatory in the Southern Hemisphere in the whole history of astronomy. To destroy this treasure-trove of observations will surely bring you lasting and increasing condemnation as the years go on.” And from the Double Star Commission, it’s President, Dr J. Dommanget, wrote, “unfortunately, as a consequence of recent re-organizations of the astronomical research in South Africa, practically all research work in the double star field in the Southern Hemisphere has been interrupted. It is imperative that immediate interest is paid by some astronomers in double star research, and effective support given to continuous observations”.

It is probably true to say that the proposed demise of the Republic Observatory caused arguments which were more heated than any in the whole story of South African astronomy”. [Copied from Moore p. 105.]

In 1972 some of the instruments were moved to Sutherland.

The opening of the Goverment Meteorological Department by Lord Milner.

The opening of the Goverment Meteorological Department by Lord Milner.

26-inch Telescope Dome and Library at the Republic Observatory.

26-inch Telescope Dome and Library at the Republic Observatory. Republic Observatory.

Republic Observatory.